Like many journalists, Raja Abdulrahim’s notebooks are filled with stories she was never able to tell. Now that she’s moving on from covering the war in Syria, the Wall Street Journal reporter, and MCJN mentor, reflects on feeling indebted to those who trusted her with their painful stories.

In the room where the Syrian family of six slept, the walls were bare except for the photo of a little girl with big blue eyes and pink pigtails held in a paper frame.

It hung like a memorial to 3-year-old Rayan who had been shot and killed by a sniper months earlier. The family was on a bus fleeing shelling in their neighborhood when gunfire interrupted their escape, sending bullets and shards of glass into the vehicle.

When I met with the family, Rayan’s mother, Najwa, was on the verge of having her sixth child. But her days were consumed with mourning the child she wasn’t able to protect even as the girl sat in her lap on the bus.

“You feel they really target the children in order to burn the hearts of the parents," Najwa told me.

Underlying this guilt is the overwhelming sense of failure that even those that made it onto the printed page have done little to alleviate the suffering.

Eight years later, her anguish has stayed with me and not only because her pain represents so many parents who have had to bury their children during the course of the Syrian war. She entrusted me with her story of suffering and I failed her; I never wrote it. Her words stayed in my notebook along with many others whose tales didn’t get their due.

Earlier this year I moved on from covering Syria after eight years of reporting on the conflict and am haunted by those stories I never told. Journalists know that not all reporting can make it onto the printed page but those untold stories can feel like an unpaid debt.

Underlying this guilt is the overwhelming sense of failure that even those that made it onto the printed page have done little to change the course of the conflict or even alleviate the suffering.

But war is about more than stories of loss. Like the absurdity and moments of black humor that perhaps surprisingly punctuate warzones but don’t usually get relayed because it might seem disrespectful. Or remembering those who helped us reporters do our jobs in a country that has been one of the most inhospitable to journalists: smuggling us in and out of the country, shepherding us along frontlines and hosting us in their homes.

It was pitch dark in the back of the jeep at the foot of a mountain on the Syria-Lebanon border as I readied to leave Damascus after two weeks of undercover reporting.

I could just barely see the outline of the rebel-cum-smuggler sitting across from me and the AK-47 rifle resting against his thigh. He was whispering a nearly frantic stream of prayers with a sense of urgency I had not heard before from a rebel fighter.

Normally the men who had taken up arms against the government had a blasé attitude even in the most dangerous situations. I didn’t share their nonchalance at the sound of artillery nearby or running across a sniper alley, but I relied on their calm demeanors to allay my own fears.

Now the anxious rebel in front of me was making me nervous. If he was afraid, I should be terrified.

Only when he lit a cigarette near the end of our trek - which moments earlier would have been too dangerous because it could have been spotted by government soldiers – did I know we were safe.

I don’t recall his exact words before we parted on the other side of the border but I remember the gist: he urged me to relay what I had seen. What went unsaid was that he was willing to risk his life so that I could do so.

Like many conflicts, the Syrian war entered into a pattern of cruel repetition and covering it began to feel like a cycle of similar stories. And as the conflict’s pace of tragedy eventually outstripped waning international interest, it felt like ever more stories were left on the cutting room floor.

Last year I interviewed a Syrian journalist who had fled from Syria to Turkey. She told me of how in 2018 she, her husband and two young children were led by a smuggler from Syria’s northwest province of Idlib. By the time I sat down with her at an outdoor café in Istanbul I had heard years of such accounts. But the details of their exodus still brought me to tears.

He urged me to relay what I had seen. What went unsaid was that he was willing to risk his life so that I could do so.

The smuggler they paid thousands of dollars to threatened to cancel their arduous mountain journey across the border if the children were awake. She gave her six-month old baby cough medicine to make him drowsy, but it wore off 30 minutes into their 4-hour trek. The baby though somehow seemed to sense that something wasn’t normal and didn’t make a sound, his eyes wide with fear.

Her other son, then 3, was on the verge of tears throughout the entire journey. “My son, God help you please don’t cry,” his mother quietly begged, trying to soothe his fears.

Hours later and safely in a vehicle on the Turkish side of the border, he burst into tears, finally letting his pent-up terror spill out. He didn’t stop crying for hours.

More than a year later, he remained scarred by the experience and remembered the journey every time they walked along Istanbul’s steep streets, turning to his mother in fear and asking, “Mama, are you taking me back to the mountain?”

We have written about so much bloodshed and grief in Syria. Somehow though this story was just as heart wrenching: two children too scared to cry.

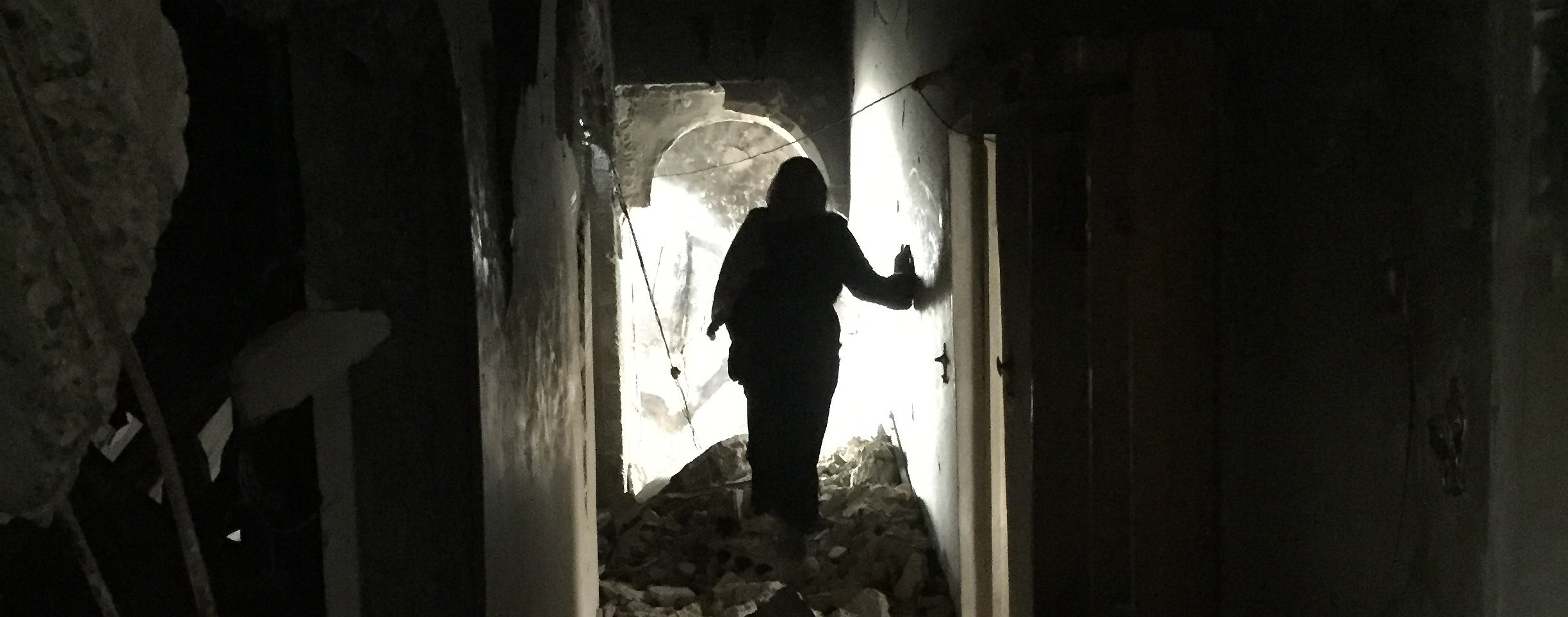

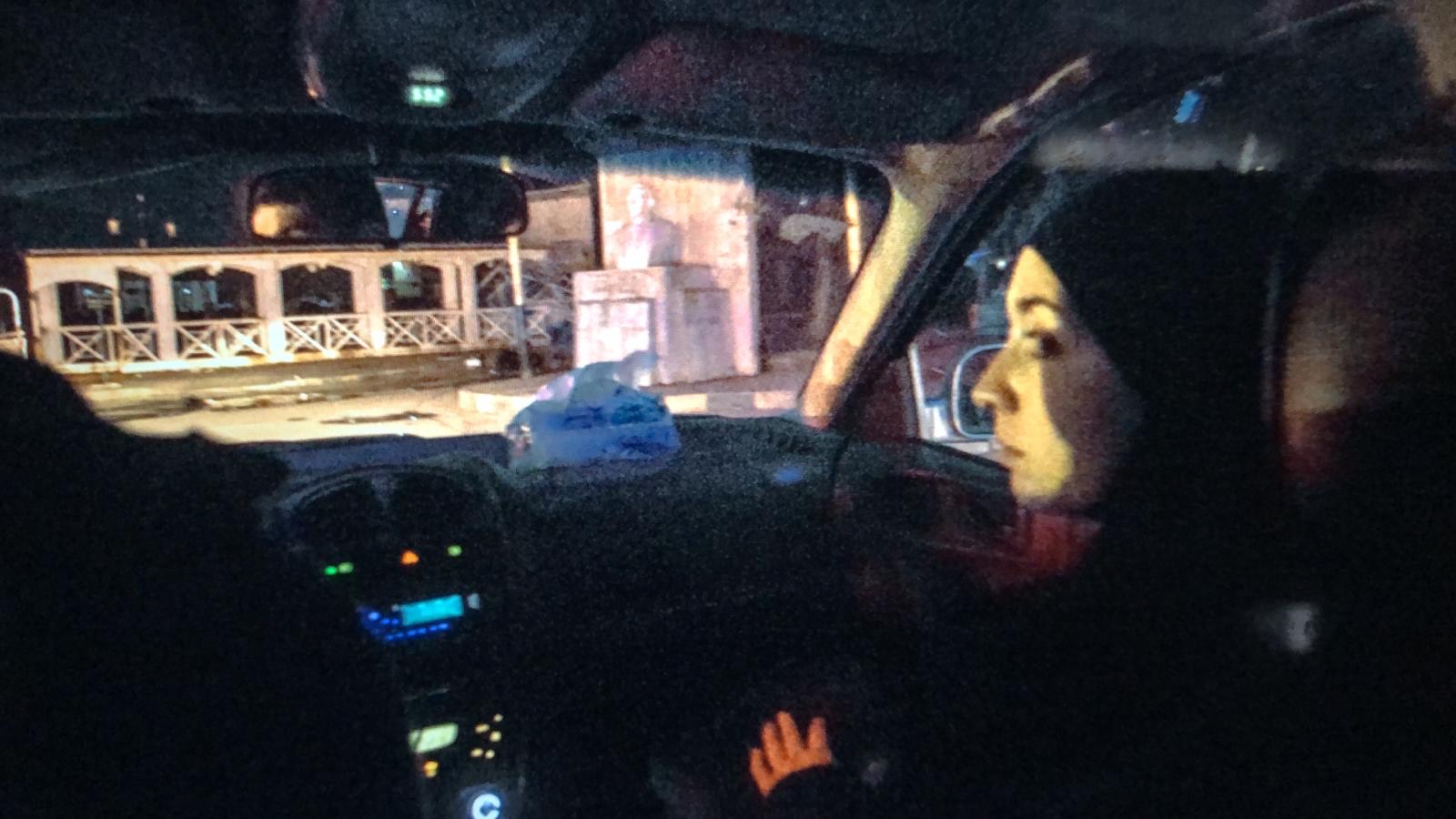

Photos:

Top: Syrian woman walking through her home in Raqqa after it was destroyed by ISIS. Middle: A rebel mourns the killing of another fighter in the streets of the Old City of Aleppo. Bottom: Raja Abdulrahim in Qamishli, by Ahmed Deeb.

All photos courtesy of Raja Abdulrahim