UK-born MCJN member Shahla Omar lost her father shortly after returning to London from a family trip to Iraqi Kurdistan. Burying him in his home town propelled her to stay on in what became a two-year assignment as a news editor and a journey of self-discovery. She is now back in London where she works as a senior journalist with The New Arab.

Cutlery clinks and the bass voices of Rudaw’s nearly all-male staff echo throughout the work canteen. I slide my way through a maze of tables with Soma, who works in the PR department. “The Number One question people ask me now is ‘where is that girl from?’”, she tells me, slightly fed up.

Most diaspora kids feel some kind of pull towards where their parents come from, but its heft and tug are different for different people

The short answer is that I’m a Kurdish woman in Kurdistan. But I’m given away by what I deliberately choose to show — my asymmetric pigtails and nails not done, a yellow football jersey, orange linen culottes and trainers — and by what I can’t help: my brown skin, my big black hair and the apprehensive look on my face. They make me look foreign.

Without getting too clichéd, I think most diaspora kids feel some kind of pull towards where their parents, grandparents and other ancestors come from, but its heft and tug are different for different people. My father died suddenly in February 2019, a few months after we’d returned to London from a trip to Kurdistan, a trip during which we’d made plans to buy a house in Sulaymaniyah. We buried him in Kurdistan, and I felt like I was being pulled, dragged along by a thick, heavy rope of duty and desire, bound up with the fate of Kurdistan.

When I was younger, I thought about becoming a journalist or a lawyer — something with words. I didn’t think I was loud enough to become a lawyer, and journalism felt too far away and abstract. I started a biomedical science degree, thinking I could transfer to training to become the pinnacle of brown success — a doctor! And even if I didn’t transfer, I’d graduate at 21 and work in a lab. I hated it, and dropped out at the end of first year. I did a French degree that taught me colonialism = Algeria and that all French people speak like Parisians do. The limited scope of what we were taught and whose stories we were told frustrated me; I joined a student campaign to include the stories and voices we could not hear, to decolonise it. I did a Masters in “Empires, Colonialism and Globalisation” at the London School of Economics to fill the gaps in my knowledge and started working at a racial justice charity. Part of its focus was telling the unheard stories, a lot like journalism.

What I learned from my family about Kurdistan and Iraq is in no way whole and it is my responsibility to spot what’s been left out, what gaps in my knowledge need to be filled

A few days after we buried my dad, my cousin told me about a job opening for an editor at Rudaw English. The new head of the English desk was not only my cousin’s friend – he was one of two reporters who wrote an in-depth story about a 2015 airstrike on a home in a Shabak village near Mosul a few years back that killed five of my relatives. I thought, yes, this is a good man, a good person to work for. A good journalist. I made the leap.

Rudaw’s newsroom is like a greenhouse. A glass wall faces the sun and your back slowly roasts while you edit news on failure to agree on a budget bill or a feature on why Iraq is everyone’s playground. At least two of the coffee puddle stains on the floor are mine. Five languages collide in the air; Kurdish, Arabic, English, Turkish, Farsi . I was the only diaspora Kurd, the only brown editor, an island. Early on, I mediated between the men, did translations, took meeting minutes, accompanied Rudaw’s foreign journalists to the internal security for their residency documents. Things eased up a little a year in, once I became features editor, and I even kind of forgot how exhausted I’d gotten. I loved editing work by local writers, especially young ones, and was lucky enough to deal personally with other in-depth stories.

Of course, before moving here from London I was never completely disconnected from Iraq and Kurdistan. I went to an Arabic school run by Iraqis, and loud conversations about politics filled my relatives’ homes most weekends (my dad used to do an impersonation of Saddam Hussein’s statue being toppled -- he’d slowly tilt to the side and whistle). But that can give you a very skewed version of what Kurdistan or Iraq are like, and the more time you spend here (living and working here, not as a visitor) the more you have to relearn things. What you learn in London is filtered through the people who were actually in Kurdistan or in Iraq, what’s important depends on experiences that have brought your family both joy and trauma. They’ve blocked out some and treasured others. What I learned from them about Kurdistan and Iraq is in no way whole and it is my responsibility to spot what’s been left out, what gaps in my knowledge need to be filled. What I learned in the two years I was in Erbil won’t fill that gap in my knowledge either.

At the time of my dad’s death, his papers said he was single and had no children. So we had to register him as married to our mum, then register him as dead, then as my father

Reporting and editing here as a diaspora Iraqi forced me to confront and examine assumptions — about Kurdish party unity in the face of Baghdad (not nearly as much as I’d thought), about the importance of those grand-scale causes that inspired my dad when he was young (as opposed to the everyday grind of feeding your family that seems to drive most people here), about what needs fixing in society and politics (which isn’t necessarily at all what my relatives who moved away think needs fixing). I also hadn’t quite anticipated that I, a West London girl, would experience culture shock. But I found I disliked Erbil. The 15-minute walk to work was a course on how to dodge cars, shop displays and palm trees planted in the middle of what looks like a pavement. The parks are all clumped together in the fancy part of town. The economic inequality, the fear to speak up for political change, the heavy-handed police presence at protests, the frequent power cuts in a country full of oil — these are depressing. (In Erbil, the heavy police, known as ’Asayish’ presence is a show of force meant to prevent protests or any kind of unrest from happening, a dare to locals who might feel like it is time to act.) Distance is distorted here. Mosul and Fadhiliya are an 80-minute drive from Erbil but feel like a different continent. There are five checkpoints between Erbil and Sulaymaniyah. The Corona pandemic warped time too, preventing me from traveling to Sharazur to see family. The bureaucracy for my own travel documents is deadening: at the time of my dad’s death, two years ago, his papers (and my mother’s) said they were single and had no children. So we had to register our dad as married to our mum, then we’ll need to register him as dead, then as my father.

The fear of speaking Kurdish faded just in time for my departure back to London, my hometown. This month, in June, I start at The New Arab. I’m thankful to my MCJN mentor, Sara Hussein, for pushing me, gently but firmly, when doubts about leaving Kurdistan for a while had me feeling stuck. I’ve been packing up my books and the winter clothes that the hot, dry winter of Kurdistan would not let me wear. I’m hoping to send them to London using the cargo service my mum’s cousin uses to send tahini produced in and named after Fadhiliya from here to the UK. I want to keep coming back, to see my friends, my family, my father’s grave. There are also stories I want to write here, a lot of them intertwined with my own, but it feels somewhat self-indulgent, like I shouldn’t use myself as a drawing board. Who knows? At my new job, perhaps I’ll be a puzzle for my co-workers again. But this time, in a different way. My family here don’t say I’m from London anymore. Instead, I’m “kchi hewleri”, the Hewleri girl, in honour of the city I lived in while in Kurdistan.

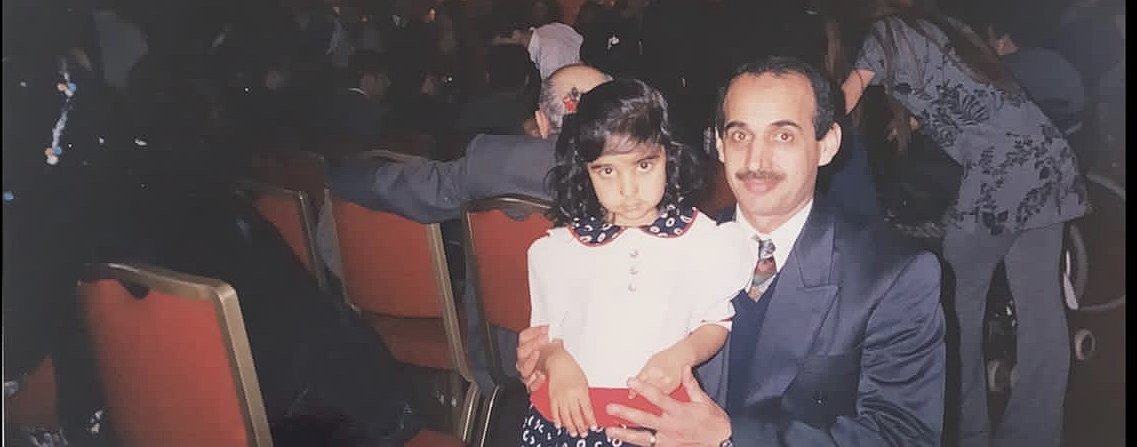

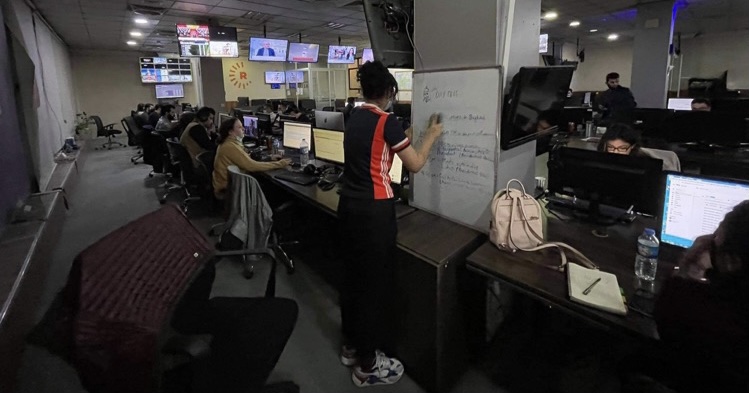

Photos (all courtesy of Shahla Omar)

Shahla Omar and her father during Nowrouz celebrations in 1999

Shahla in the newsroom of Rudaw network with her signature football jersey

A house in the village of Fadhiliya, near Mosul, where Shahla's relatives were killed by an airstrike widely suspected to have been conducted by the US-led coalition in 2015. Shahla took this photo in December 2019