Dalia Khamissy, a Lebanon-born photographer and MCJN mentor, has made a career for herself out of documenting human suffering and paying tribute to people who suffered from Lebanon’s multiple tragedies. Her Instagram account features a stream of photos and stories from the families of an estimated 17,000 civilians who went missing during Lebanon’s Civil War between 1975 and 1990, and Syrian refugees who fled the war in their country and live in poverty and desolation in Lebanon. Now, she is working on a project with the “Legal Agenda”, an NGO for promoting the rule of law and institutional accountability, to document the stories of the victims of Beirut’s Port blast, which took place on August 4th 2020.

Where were you when the Beirut Port explosion took place on August 4th, 2020?

I don’t think anyone can forget where he/she was at that specific moment. At 18:08 pm, I was at home talking to a friend over the phone. She was driving down a road not far from the port itself. She told me she could see fire, and then we heard the double explosion. We both screamed and her line was cut off for a while.

Luckily there was no damage to my flat - my windows were open at that moment. I had a plate of food in my lap, and I could see the food flying, in slow motion, out of the plate and then splattering on the floor. My cat ran around the room in panic, but everything felt so slow at that moment. I live on the third floor but I could feel particles of sand rising from a bush behind the building all the way up, and hitting me on my head and shoulders from the window behind me.

Many of us, outside Lebanon, were informed about the explosion in real time because people were posting photos and videos live on social media. At what moment did you decide to take out your camera and start shooting?

I feel we are witnessing another amnesty, similar to the Civil War. If we don't act now, we'll still be asking questions and looking for answers in 15 years.

I didn’t even go to the balcony when the explosion happened. I messaged my family to tell them that I was OK, then I turned the TV on and saw the first footage of the blast.

That same day, at night, an agency contacted me and asked me to work for them, but I could not get myself out of the house. The second day I accepted an assignment from the British Red Cross only because it was for a fundraising campaign.

On the third day after the blast, the editor of Le Monde contacted me to work with them. I knew the two journalists I was going to work with, and that is why I accepted the month-long assignment. I was only able to do this because I was accompanying them and I wasn’t going on my own. Otherwise, it would have been very difficult for me to go out and shoot on my own.

You are currently working on a new assignment with Legal Agenda to document the stories of the blast victims. Tell us more about that.

Legal Agenda got in touch with me because they wanted a photographer who could tell the stories of the families of the victims of the blast. I immediately accepted and I proposed a project similar to the stories I post on my Instagram account about the families of those missing since the Lebanese Civil War, but with longer text, videos and sound.

I felt that I had done enough work with media outlets, and now I wanted to go deeper into the stories of the families, to show how their lives have changed in the aftermath of the blast, which is something the media doesn’t focus on much. At the time, the fighting had also erupted in the Nagorno-Karabakh region and the attention shifted there, so there wasn’t much interest in Lebanon and the aftermath of the blast anymore.

I was starting to feel that we were witnessing another amnesty, similar to the one we witnessed after the Civil War, and if we did not act now, we would still be asking questions and looking for answers in 15 years, and trying to find justice for the victims and their families. I also felt that people were trying to move on and that the families of the victims were being left alone to deal with their tragedies and losses.

In the Arab world, we often deal with victims as just numbers. When Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri was assassinated in 2005, it was reported that 20 others died with him. But who were these people, what were their names, and why did we only care about Hariri? Victims are not numbers, and we cannot have another amnesty for those responsible for this explosion, as we did for those who led the Civil War.

This project is still in its early stages. I have already visited some of the families. Every time I go to their homes, I take my camera with me, but I haven’t yet taken any pictures. For now, I’m just listening to them.

How is this project different from “The Missing of Lebanon”, the project you started many years ago to document the stories of the families of some of the estimated 17,000 civilians who went missing during the Civil War?

I cannot ask a mother who’s just lost her son in the blast to pose for me while holding a photo of him. Not just yet.

The key difference is that the Port explosion has just happened, whereas the Civil War ended more than 30 years ago. So the way people talk about their pain and anguish is different. There is no doubt that the families of the missing are still damaged and hurting, but they have become used to talking about their loved ones. The things they tell you are different.

When I interview the victims of the explosion, their pain affects me even more because it’s still present and they’re not used to it yet. I cannot, for example, ask a mother who’s just lost her son in the blast to pose for me while holding a photo of him. Not just yet. This is why it’s taking me longer to take photos for the Legal Agenda project.

One family lost their son in the explosion, and some members are uncomfortable talking in front of the others. I spoke with the father for 25 minutes, his two remaining children were in the same room listening to him speaking and crying. But when his wife walked in, he asked me to stop the interview. On the other hand, his children are uncomfortable talking in front of him or their mother, but they are willing to speak to me alone.

What I find so overwhelming is that the families trust me with their stories, and despite their pain they are so warm and generous. They insist on inviting me for lunch or to stay the night if their home is far away. The first time I went to one family’s house, I had lunch with them, but I couldn’t eat the bread because I’m allergic to wheat. The next time I went there, their son had bought four different kinds of bread for me to choose from because they were worried about my allergies. When I told them that I like walnuts, they sent me home with three kilos’ worth of walnuts from their trees. I don’t know if other journalists experience the same kindness and generosity, but I find it so warm and amazing.

Previously, you’ve talked openly with The Marie Colvin Journalists’ Network about the effect your work has had on your emotional health. You mentioned that you experienced PTSD (during the 2006 war with Israel) and extreme cumulative stress disorder (while working on the Missing of Lebanon.) How do you approach your work now while maintaining your emotional wellbeing as well?

During the 2006 war, I couldn’t talk or communicate with anyone who wasn’t living the same experience that I was living. I could only talk with journalists and people who were working on the ground because we had a shared experience.

I’m not a hero. I'm a human being and a victim of the blast too, and I cry with the families. How could you not cry when you hear such horrible stories of loss?

The other day, I went to interview another family and I cried with the mother. That day I was supposed to go see my mother but I decided not to because I wasn’t feeling well after the interview. I just went home, sat alone for a while, cried a bit and then when I felt better, I went to meet friends.

I try to take care of myself and I’m trying to go back to exercising and fixing things in my apartment, which helps a lot. If small self-care measures do not work, I will go see a therapist because I am more aware now of the trauma caused by working on such topics and I do not want to go through the traumas that I had before.

I’m not a hero and I am not acting like one. I am a human being and a victim of the blast too, and I cry sometimes with the families. How could you not cry when you hear such horrible stories of loss?

Are you hopeful that your work this time could lead to change, or lead to some sort of accountability? Or is this too ambitious?

Given that I’m doing this in partnership with Legal Agenda, who work on the many social issues in the country, and I am supporting them as they try to achieve legal change, I do have some hope.

But I also feel that this project is a tribute to the victims because their families are so worried that people might forget quickly. The Lebanese love to think of themselves as resilient people who can move on quickly and go back to their normal lives, but the families don’t want their sons and daughters to be forgotten so quickly.

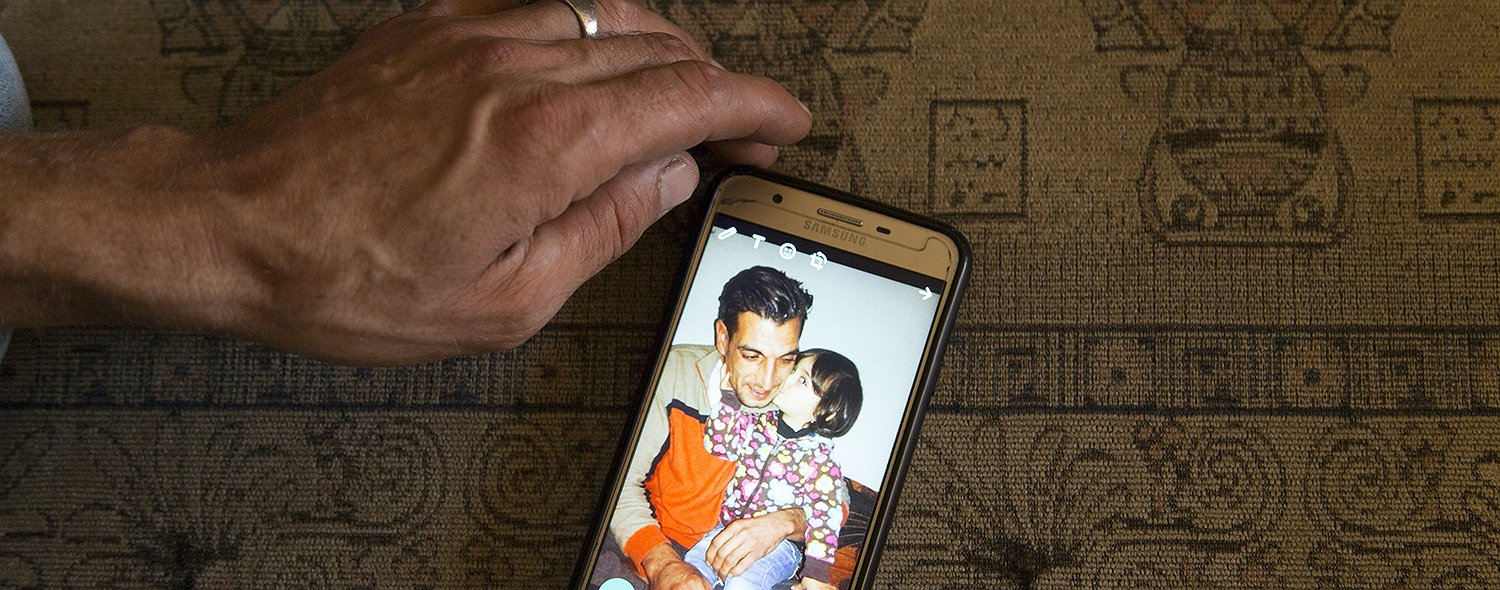

Photos: 1. Samer, a Syrian worker, and his daughter Bissane, who died of her wounds days after the port explosion in Beirut on Aug 4th 2020. 2. Samer sitting in his friend's apartment in the Qarantina district in Beirut. 3. Photographer and MCJN mentor Dalia Khamissy.