Ghada Al Sheikh is a Jordanian journalist working for Al Ghad, a local daily. She is also a contributor for Raseef22 and has a large audience on social media.

I contribute political and social stories from Jordan to Raseef22. Although this wasn’t the first time that an article of mine stirred controversy with the readers, it was the first time that I’ve received death threats, indirectly, and was so afraid that I’ve had to ask Raseef22 to take down the article. They were understanding and willing to oblige.

People accused me of promoting homosexuality in Jordan. I am sure that 90% of those who attacked me didn’t even bother to read the entire article.

In June 2020, a few days after the Egyptian queer activist Sara Hijazi took her own life, a group of activists drew a large graffiti portrait of Sara in downtown Amman with the phrase “... but I forgive”, which was taken from her farewell letter. The Municipality of Amman was quick to remove the graffiti and the story was widely debated on social media. I proposed writing an article about this for Raseef22 and interviewed one of the artists who drew the graffiti. I interviewed a young man who is a member of a group for queers in Jordan. We talked about the challenges facing the queer community in Jordan and about his personal experience. It was such an interesting interview and it raised a lot of other ideas that I would like to write about, but this is now put on hold.

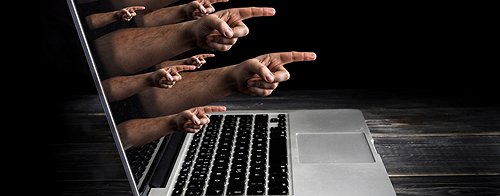

When the article was published, I was taken aback by the deluge of tweets and messages attacking me and the website. People accused me of promoting homosexuality in Jordan, and some claimed that I was gay, which I’m not. I am sure that 90% of those who attacked me didn’t even bother to read the entire article. Had they done so, they would’ve realised that I wasn’t trying to stir controversy on purpose. It is true that I am daring in my choice of topics and I do want to break taboos, but I don’t do this to clash with my audience. I honestly feel the reaction to this article was hugely out of proportion.

But when I received indirect and implied death threats, I asked Raseef22 to take down the article. They did so and published a statement to express their solidarity with me. This wasn’t enough to put an end to the attacks. The hashtag #BlockRaseef22 was trending for 4-5 days and the attacks on me would not stop. People would call me names and threaten to hurt me.

After several days of relentless attacks, I posted a tweet saying that I would resort to the law if they didn’t stop. The moment I posted that tweet, the attacks stopped.

I had to keep a low profile – I stopped tweeting and I even had to pretend that I had a boyfriend to show that I was not gay. I would only leave the house to go to work. I wore a face mask all the time and had to look behind my shoulder everytime I got out of the car.

Although I felt the threats were nothing more than just people venting off, some friends warned me and said these threats were serious. They reminded me that this was what happened with Nahed Hattar, a Jordanian writer who was killed in September 2016 because he shared a caricature that some felt was blasphemous on his Facebook page.

I decided to get legal advice, and a lawyer told me that the tweets against me are considered a violation of Article 11 of Jordan’s Electronic Crimes Law, as they are considered to be libel and slander and carry a minimum sentence of three months in prison, and a fine of JOD 100-2000 ($140-2800).

As a Jordanian journalist and activist, I’ve always been fiercely critical of Article no.11 and so resorting to it was a difficult decision for me. The Article is vaguely worded and the Jordanian authorities have been using it as a pretext for gagging activists and human rights’ defenders. Nevertheless, I didn’t have another choice to protect myself. After several days of relentless attacks on me and Raseef22, I posted a tweet saying that I have copies of all the attacks on me and that I would resort to the law if they didn’t stop. The moment I posted that tweet, the attacks stopped. Several people even rushed to delete their previous tweets.

I will not change the way I write and will not exercise any self-censorship.

I’ve been a journalist for more than 12 years, and what saddens me the most is that those who attacked me were some of my most ardent supporters and followers. They used to send me story ideas and would follow my work diligently, but after this article was published they turned against me, and now they’ve gone back to following me as if nothing happened. One of the attackers used to be a trusted source. When the campaign against me stopped, I wrote to him and confronted him with what he did, but to this day he hasn’t responded.

My dedication to my work has been at the expense of my personal life, and I’ve started to wonder if there is a point to what I do. I’m not as active on Twitter as I used to be, but my sincere followers know that I’m still out there in the field and that I pursue causes that I care about, such as the teachers’ strike (they took to the streets again as the government hasn’t delivered on its promises to them last year). But I don’t have to prove anything to anyone, which is why I don’t tweet so much anymore.

My advice to members of The Marie Colvin Journalists' Network is to realise that it is difficult to avoid things like this from happening if they choose to write about sensitive and controversial topics. So the most important thing is make sure that all their articles are legally sound. I knew that my article about the graffiti in downtown Amman did not violate the law in any way. I will not change the way I write and will not exercise any self-censorship. And despite everything that happened, I still believe that Article no.11 should be rescinded.

Samia Al Aghbary is a journalist and editor with Al Thawra newspaper in Yemen. She hails from Ta’iz and currently lives in Cairo.

Political parties in Yemen differ over everything, except their methods in targeting women. If a woman writes an opinion piece that they don’t like, they don’t discuss her ideas as they do when the writer is a man. Instead of debating her thoughts and opinions, they accuse her of immorality, libel and slander her, and they incite the public against her.

They focus on her private life and throw all sorts of obscenities at her to hurt and silence her. I was called a “pleasure-seeking whore”, a “spinster”, and a “hag”. They said I go to bars and brothels.

I was called a “pleasure-seeking whore”, a “spinster”, and a “hag”. They said I go to bars and brothels.

In 2006, at the beginning of my career, I wrote an opinion piece for alwahdawi.net about the late Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh’s decision to run for elections after he had pledged not to do so. I described what happened as “theatre” and I mentioned that his party had forced people to go out to the streets and chant for Saleh. In response, Al Dustour newspaper, which was affiliated with Saleh, published a direct letter to me, and it was very bad. They said I was not qualified to write about politics, and should write instead about perfumes and food, and they claimed that I had immoral relationships with men. This article could have broken any other female journalist, but my father stood by me and pushed me to file a case against the paper. I remember he told me: “Don’t break down now, because if you do, you will never be able to get back up again.” The court ruled in my favour and the paper had to pay a fine and published an apology.

In 2011, Saleh’s regime started a new round of campaigns to slander female journalists and activists on social media. I was among those targeted, as several accounts on Facebook - both real and fake - published my photos with nasty captions, such as “whore” and “hag”, “desperate for a husband” and others.

My father told me: “Don’t break down now, because if you do, you will never be able to get back up again.”

After the revolution led to the fall of Saleh’s regime, in 2013, I gave a speech in the city of Damt, on the 10th anniversary of the assassination of Jarallah Omar, the deputy secretary general of the Yemeni Socialist Party, in which I criticised the Muslim Brotherhood. Subsequently, a member of the Yemeni Congregation for Reform, which is affiliated with the Brotherhood, filed a case against me, accusing me of “blasphemy and ridiculing religion”. The case did not go ahead because war broke out in Yemen, but the campaigns continued against me on social media. They would mock my clothes and appearance and social status. During that time, I also received death threats from anonymous sources, and I couldn’t leave the house without a face veil to conceal my identity.

In 2014, it was the Houthis’ turn to attack me because I was critical of them as well, and they pretty much used the same words and tactics of their predecessors. Unfortunately, in all of these cases, many female journalists and activists also took part in the campaigns against me and other women. For them, loyalty to the party and group biases took precedent over solidarity with their female colleagues.

Most of the time, I control myself and refuse to interact with these campaigns. Unfortunately, there are no laws to regulate social media and the internet in Yemen, and there is no state or judicial system that I could turn to now as I did against Al Dustour newspaper in 2007. I could’ve broken down in the beginning of my career, had it not been for my father and friends who supported me and helped me face all of this bullying. This is my advice to any female journalist who gets bullied in this way; be confident and don’t let such campaigns break you.